Langston Hughes loved music. And he especially loved the blues. Learning that Chicago’s esteemed Black Ensemble Theater (BE) would be presenting a play profiling Hughes’s life naturally generated lofty expectations. At last a contemporary Black performance venue specializing in musical theater would be taking on this neglected literary giant.

My Brother Langston now playing at the theater does a valiant job painting the highlights of Hughes’s life and spectacular career. Fiercely intelligent and remarkably gifted, even as a teen Hughes knew he wanted to do what no other Black man had ever done in America; make a living solely through his writing. That driving aspiration and the torrent of obstacles he faced in pursuit of it don’t come through as well as they might in this effort. Biography, whether theatrical or literary, can choose what it emphasizes provided key facts and time sequences remain true. In important ways, My Brother Langston does that.

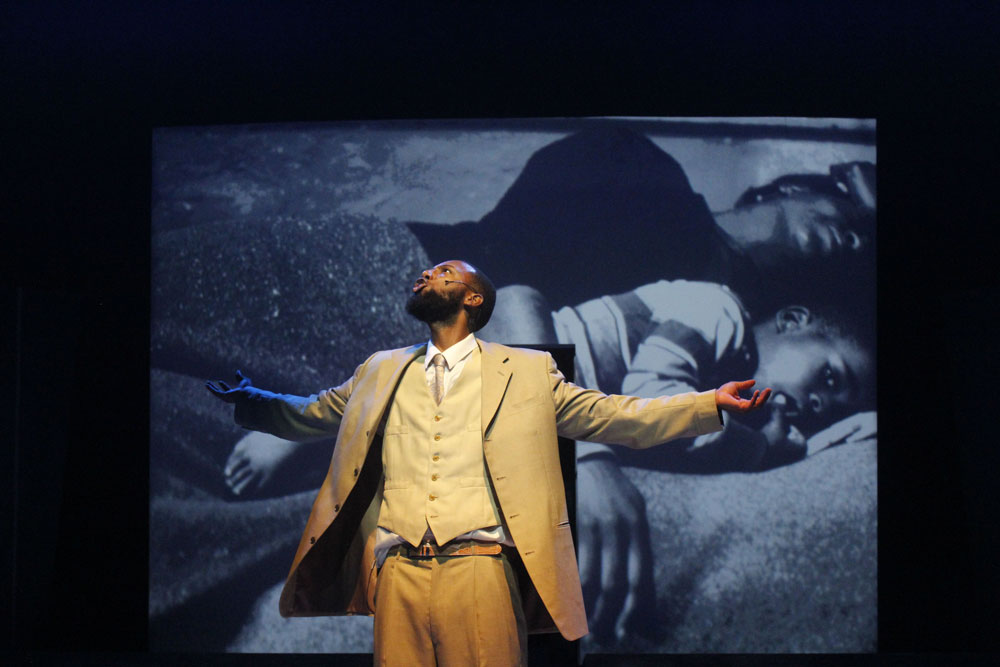

Told in the first person, Chris Taylor as Langston acts as a tour guide to his own life. It’s through his reflections and flashbacks that we experience crucial markers along Hughes’s journey and meet the people who helped shape him.

Brimming with youthful warmth and earnestness, Taylor is wonderful in his role as a young man charting a path for himself in the world. Beset with obstructions and full of rare promise, Taylor’s embodiment of Hughes engages our concern and leaves us with the confidence that he has the courage to prevail. In every elemental way, Langston Hughes was alone throughout his life. Sent to live with his grandmother in his very early years, his attachments to his parents would never become close. My Brother Langston explores the reasons for that distance and finds both his mother and father wanting. His mother, Carrie (Reneisha Jenkins), loved the arts and nurtured a desire to perform. She was also locked in a system that thwarted Black potential, talent or ambition; leaving her to subsist on the meager earnings of a domestic. By becoming a landowner in Mexico, Hughes’s father rejected his race and the confines America imposed on him for being Black in the United States. A hard, pragmatic man who parented by edict, he inevitably earned the hatred of his son. Central to their discord was their opposing views on how they saw themselves as Black people in a repressive culture. In his refusal to be stereotyped or subjugated, Hughes father first turned his back on his own identity and then chose to expatriate. The lessons Langston learned growing up with his grandmother and observing the lives of the Black people around him taught him a far different lesson. He could see the strength, wisdom and integrity it took to survive in a closed society. That perspective left him marveling at the fortitude needed to chisel one’s way to either the next day or the next rung; cementing a lifetime of admiration, respect and pride for his community.

Andre’ Teamer as James (Jim) Hughes, vividly captured the brutally noxious spirit of Langston’s father. Vitriol has a way of telegraphing brightly from the stage. In My Brother Langston, the younger Hughes’s inner resolve and belief in his own abilities, the counterforces to his father’s negativity; do not register as well as his father’s animus. In fact, they’re hardly discernible. One of Langston Hughes most notable achievements is that he wrote as a Black man for Black people. Because his aim was to be read by people of his own race, the tenor of his writing was never that of the observer or chronicler. Although most renowned as a poet, by writing short stories, plays, newspaper columns and lyrics for music, he proved himself prolific in many literary forms. Paramount in his intentions in all of them was to portray Black life with dignity and to employ an honesty missing on America’s literary landscape during the first decades of the twentieth century. His success in accomplishing that goal is one of the reasons he’s celebrated today.

Very few lives can compare to the fullness and depth of Langston Hughes. His interests, curiosity, talent and frustration with codified racial discrimination all spurred his desire to travel and learn about the world. BE’s theatrical excursion into his life concentrates on Hughes’s earlier years; his childhood, youth and the span of years that saw his rise to fame as a writer and as a standard bearer. My Brother Langston offers a feel for Harlem during the height of its cultural renaissance and shares how Hughes fit into that vibrant mosaic of music, literature and art. A magnet for the best and the brightest, icons of the period like Hughes crossed one another’s paths in New York’s legendary borough just when their stars were on the ascent. This story scraps against the relationship between Hughes and fellow poet, Countee Cullen. That there was any romantic or sexual involvement between the two is a contentious question. Biographer Arnold Rampersad acknowledges Hughes’s sexuality was often assumed but believes it never to have been confirmed. This reflection on Hughes’s life also lifts the veil on the manipulative machinations of his first patron, Charlotte Mason, who insisted everyone on the receiving end of her largess call her Godmother. De’Jah Jervai’s managed the role as Godmother with impressive assurance. The thick condescension she portrayed may have been mildly exaggerated; but the way Jerval translated Mason’s ruthless flexing of power was not.

Nolan Robinson as Hughes younger brother Gwyn was a spark of lightness and joy in a story that pushed so determinedly to achieve triumph. The son of Hughes’s mother’s second husband, there was no blood connection between Gwyn and Langston. That absence didn’t impact the solidity of their bond. Hughes was a doting big brother and Gwyn was a proud younger one, proclaiming Hughes’s successes and accomplishments whenever he had the chance. “My brother, Langston is a famous writer!” “My brother, Langston, has a new play opening in New York!” His boasts spoke for the millions who trusted Hughes to honestly reveal the humanity of their lives to the world.

Although prominent, music didn’t drive the storyline as intensely as it often does in a BE performance. Serving more to highlight an era and provide uplift, its contributions added period context and emotional color. Along with the beautiful vintage photographs projected at the rear of the stage, the audience gained a sensory understanding of the age Hughes occupied.

My Brother Langston

Through September 18th, 2022

Black Ensemble Theater

4450 N. Clark St.

Chicago, IL