After seeing Where We Belong, it’s clear some one-man shows are made of just three things; courage, intelligence and an irrepressible spark of passion. That’s certainly true for this revealing and highly satisfying effort in the Goodman’s Owen Theatre. More accurately a one woman autobiographical exposé about its creator and performer, Madeline Sayet, Where We Belong manages to be both epic and supremely human as it shows us the cost of discovering self.

Like many of us, Sayet’s origin story caused her to live much of her extraordinary life on an uncomfortable fence. A fence that immigrants and minorities know well. Two different ways of life exist on either side and she, like other people viewed as “them”, must navigate both sides to attain a semblance of self-actualization and to survive. For Sayet, who’s Mohegan, the rigors of navigating her Native culture and that of her country are daunting and never ending. She’s absorbed the lessons her family has instilled in her. Lessons that have given her a deep appreciation for her heritage and culture. A proud Mohegan, steeped in her tribal history and attentive to its belief systems, her respect and reverence for her lineage virtually glows. It’s the kind of pride that shapes identity.

But her other world also has its powers. Becoming a lover of Shakespeare early in her life, she held on to and nurtured this interest; eventually deciding to pursue a doctorate on Shakespeare in London. We catch up her just as she’s explaining how she got to this point. She’ll go on to dissect what it feels like to place yourself in the ideological core of those who colonized and subjugated your forebears.

Through her candor and engaging energy, we easily connect with her spirit and her dilemma. It’s that bond that makes the time spent with her and her absorbing story so rewarding. The amount of insight and knowledge she shares about her Mohegan culture vividly expands our understanding of the people who made America home long before tall ships touched these shores. She introduces us to worldviews that are not only startling, but also imminently plausible as they model options for establishing democratic principles. Evidently the founding fathers also took notice of precepts embedded in Native cultures. Our own form of government is influenced by Native American theory. The Iroquois Confederacy provided “a real-life example of some the political concepts the framers were interested in adopting in the United States”. With that kind of knowledge tucked away in your consciousness, it was jarring to hear Sayet talk about wanting to be, or finding “somewhere I’m not hated for being me”.

Thankfully her back up team had equipped her with the skills to climb out of erasure holes like that. Listening to how Sayet’s mother and aunts used voices of power, of defiant assertion, to push back against biased history in standard school curriculum; revealed how committed they are in doing much more than merely surviving. They’re determined to preserve the identity of the wolf people and insure any narrative regarding them approaches balance. It’s a huge task. The Mohegans modest numbers means everyone’s dedicated commitment is needed to succeed.

Where We Belong underscores the importance of winning that fight. Sayet’s admits her academic sojourn in London may have been a way to take a reprieve from the battle. A chance to relieve the pressure of doing the myriad things necessary of achieving wholeness like working to fully restore the language. Like other tribes, fluent speakers of the Native tongue have already disappeared or are dwindling. Studying Shakespeare would allow her to revel in a language virtually immune from the threat of extinction. But even in England, as she tried to learn how indigenous Americans are regarded by the colonizer, painful realities were waiting. The examples she presented stood as they own reasons for redress.

After fighting didn’t deter English colonial encroachments and diplomacy failed to preserve tribal autonomy, Native delegations traveled to England to appeal directly to the Crown when the suffering of their people became profound. For Mahomet Weyonomon, Sachem of the Mohegan, that audience would never happen. Small pox, death and an ignoble burial became the effort’s outcome. In museums, she learned hundreds of skeletal remains of Native Americans were degradingly boxed away in conscious disregard of their humanity.

Sayet naturally experiences the hurt, anger and frustration revelations like these create. So do we through the way she recounts them. But it’s the way she uses this knowledge as council and as inspiration to guide her future that ultimately defines her and her performance.

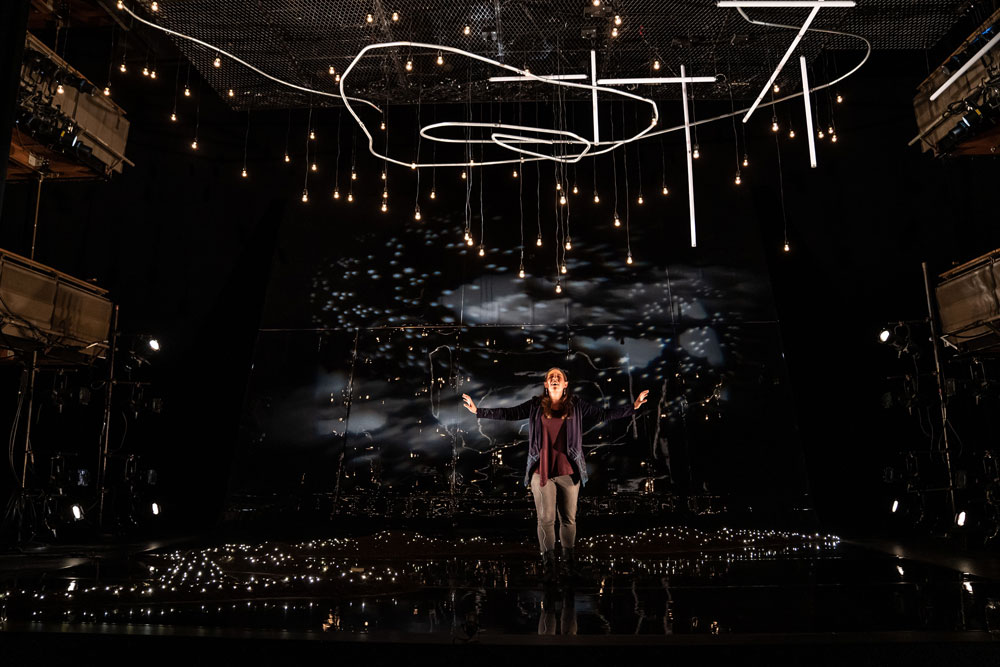

Production designer Hao Bai enjoys experimenting with “how visuals can provoke what we hear”. Bai’s often bold and always imaginative use of lighting to help Sayet tell her story proved its own triumph.

Where We Belong

Through July 24, 2022

Goodman’s Owen Theater

170 N. Dearborn Street

Chicago, IL 60601