The seed of greatness often shows itself early. Given the right environment and care, it grows to capture the imagination of the globe. The gifts of Georgia O’Keeffe, an artist best known for her magnificent paintings of the Southwest, bones and flowers, were recognized while she was very young. Encouraged by the support she received at home on a Wisconsin dairy farm, and later driven by the continued encouragement of teachers, the manifestations of her outsized talent would go on to transfix the world. On one level, O’Keeffe’s storied artistic career would prove that the best American art stands on equal footing with the best European art. An idea that was vehemently challenged when she began her professional career nearly 100 years ago in the 1920s. And on another, she made it irrefutable that artistic talent, and personal ambition, are gender free.

Georgia O’Keeffe: “My New Yorks”, now on exhibition at the Art Institute, rekindles the awe in seeing the power of her work. It also presents a fresh chance to marvel at how she translates what she sees and feels onto a painter’s canvas. Like artists from any medium, O’Keeffe was influenced by mentors and other artists whose work she admired. Their impact would eventually cause her to migrate away from purely representational art and veer toward modernist and abstract approaches. Both provided an avenue to inject her personal and organically reflexive responses to the objects and scenery she painted. Impressed by the work resulting from this shift away from pure realism, New York photographer and gallerist, Alfred Stieglitz, began showing her work in his avant-garde gallery, 291. That collaboration would prove pivotal and become the basis for much of the work seen in this exhibition.

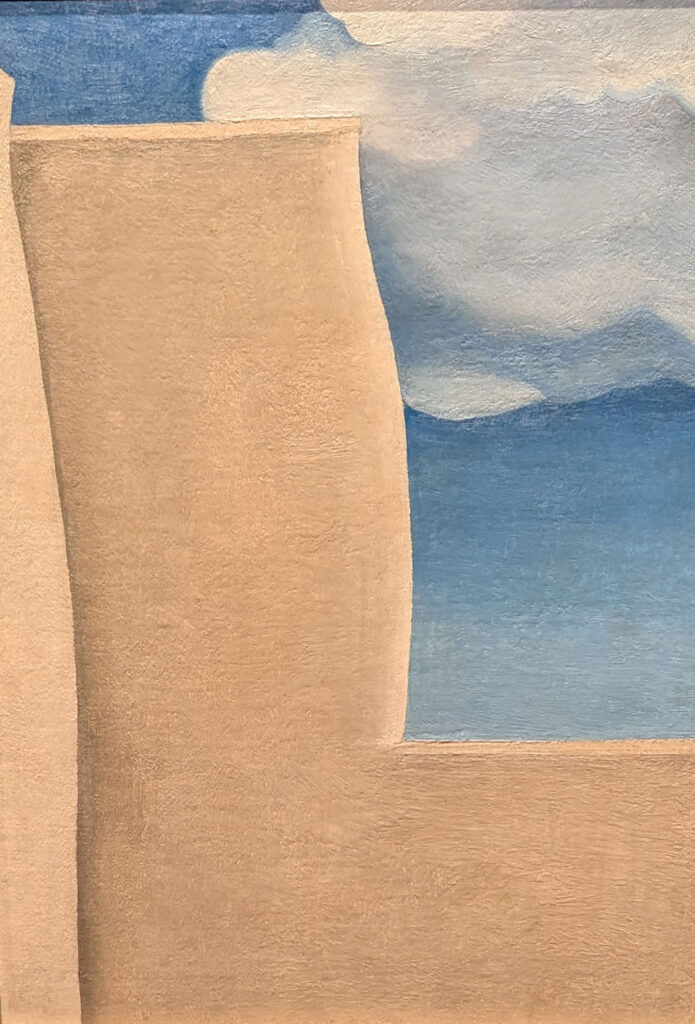

Stieglitz would go on to sponsor O’Keeffe’s relocation to New York. The two would later marry. “My New Yorks” revels in the work that came from that period and is the term she used in describing the bounty produced from it. During that time, O’Keeffe turned her perceptive eye to the city itself and how its brawn and scale relate to the natural world. Eventually taking up seasonal accommodations in what was then the tallest and most luxurious residential building in New York, The Shelton Hotel, she allowed her panoramic views to act as both muse and subject. Combined with her solitary walks around the city, she indulged her imagination and created remarkable images that enhance our appreciation for the distinctive beauty found only in metropolitan cityscapes. “My New Yorks” chronicles her travels and interests beyond the city as well. Paintings from the couple’s estate in Lake George near Adirondack Park are also included in addition to several from their early excursions to the Southwest. One of them, Ranchos Church No. 3 stops you cold with its stark purity. A simple rendering of a closeup view of adobe walls against a luminous blue sky, it places the glory of nature and of majesty of architecture on an equal plane.

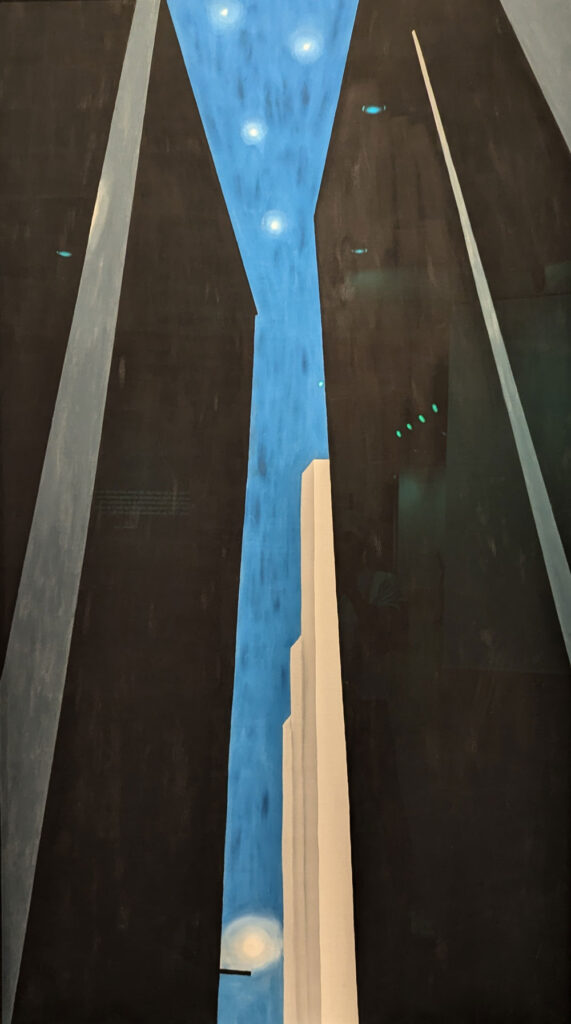

That dynamic balance can be seen running through many of the works in this surprisingly rich and wonderfully fulfilling show. New York Street with Moon, completed in 1925, has that same aura of sublime calm and absorbing intensity as Rancho Church No. 3. But here there are more things that attract and hold the eye. Devoid of people, buildings and sky remain dominant. Both are more majestic in presence and responsive impact. Night is just giving way day. A streetlight still glows, its radiance complemented by the serenity of a luminant full moon. Massive buildings the color of deep ochre push up, threatening to block the sky with their bulk. Ultimately, a balance is reached between the constructs of man and the natural world that keeps visitors captivated by the harmony they achieve together. She uses the same approach, and with the intent of arousing similar sensibilities, in City Night in 1926. Something about that piece may have seemed incomplete because she revisited it again in 1970 to add more expressive detail and to present it on a larger scale. The end result, Untitled (City Night), counts as a tour de force in its commentary on the city’s physical might.

O’Keeffe famously enjoyed freeing herself of boundaries when it came to the way she created her art. “I’m always swinging from one thing to the other (and) see no reason why abstract and realistic art can’t live side by side”, she declared in 1965. The paintings in this collection reflect that openness through the spellbinding images that result from it. Abstraction Blue (1927), a tranquil fantasy of soft color and quiet movement, leaves the world of realism entirely to offer a point of view couched completely in the imagination. It’s mood, character and impression are all totally counter to another purely abstract piece, From the Lake, No. I, that she completed a few years earlier. Translating nature to abstract forms, she creates a conception of vast expanses of water in violent turmoil. Angry, powerful and beautiful, sky and water merge into a single omnipotent force. Realism would not be disposed to deliver the same message of ravishing grandeur. Approaching her objectives through an interpretative lens, O’Keeffe is able to tap directly into our primal responses when we see nature in uncontrolled tumult.

Paintings capturing the bustling commercial activity on the East River provided a new and unique perspective of the city. In these images realism reigns and provides a detailed view of industrial muscle. In Pink Dish, Green Leaves (1928-29) she changes the mood and alters the tone by making the expansive vista outside her window the muted backdrop of a still life.

At every turn, it feels as if you’re seeing a new side of a colossal talent. And when you arrive at the end, your first impulse will be to start all over again to imbed these matchless images into your memory.

Georgia O’Keeffe: “My New Yorks”

Through September 22, 2024

Art Institute of Chicago

111 S. Michigan Ave.

Chicago, IL 60603