Two southern cities show how the arts can be a powerful lens to view both the past and its relevance to the present. This Land Calls Us Home, a special exhibition at Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport, honors the legacy of the indigenous tribes that once dominated America’s Southeast. The relationship Native Americans have with their ancestral homelands have evolved over time and don’t focus exclusively on a history of injustice. This Land Calls Us Home attempts to create a more contemporary narrative while also providing astonishing visual experiences to travelers passing through the airport’s T terminal. Some of the art work focus on community and autonomy. Other pieces highlight heritage, legacy, nature, communication and diversity. The breadth of their commentary through art means that the work covers a range of mediums and that their expressions carry a distinctly contemporary flavor.

Affirming the continued presence of indigenous people in their native lands stands as a key goal of the exhibition. Because Native Americans now make up such a small percentage of the population, our collective mindset views them as figures from the past. This Land Calls Us Home acts as a way to dispel this notion. It also sheds insight into how, through the vision of artists, indigenous Americans see themselves individually, collectively and in context with the wider world. Heritage plays a key role in each of these appraisals.

Items of prestige and status, Native American men, including those in the Southeast Woodlands of Georgia and neighboring states, often wore elaborately beaded pouches known as bandoliers. Uprooted In the 1820’s and 30s, relocated to Oklahoma Indian Territory and severed from the means to sustain their traditions, the art of creating such exquisite beadwork nearly disappeared. A resurgence of interest within tribes and Native American communities to celebrate heritage included a return to bygone crafts and craftsmanship. Cherokee beadwork had all but vanished by the 1980s until it was revived by Martha Berry. Carolyn Pallett’s, Revival Takes Root, is one example of custom restored. A student of Berry, Pallett gives her gives tradition a contemporary twist by incorporating organic and other creative motifs into her designs.

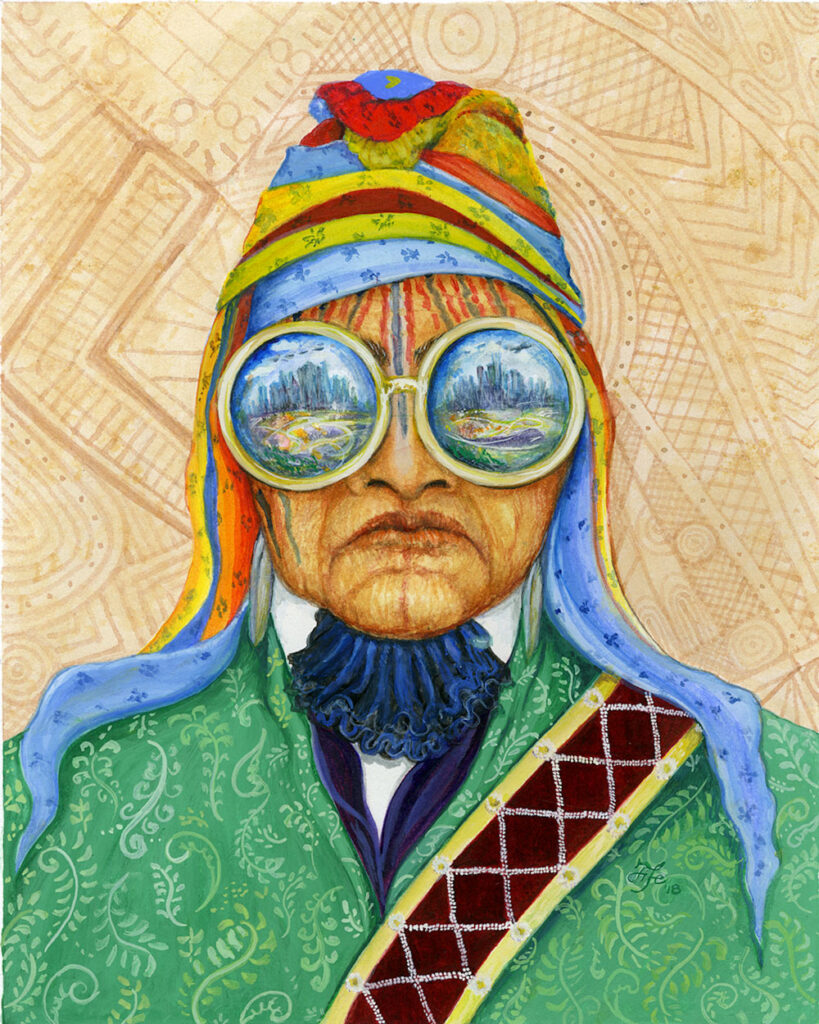

Striking and resonating as distinctly modern, Jimmie Carole Fife’s, I See the Future, brilliantly blends the past and present. A portrait based on the Upper Creek Chief of Eufaula, Yoholo Micco, it depicts a man in 1800’s dress staring into the future through glasses that look like binoculars. Radiant and light, the portrait’s colors speak the language of optimism and promise; in direct counterbalance to the subject’s serene solemnity.

Hundreds of miles away in Charleston, South Carolina, a new museum leans on high resolution technology and written narration, as well as artifacts; to recall, commemorate and reconcile one of the country’s most egregious moral failures, the slave trade and the system it perpetrated. Gadsden’s Wharf, where the International African American Museum (IAAM) now sits, holds a unique place in history. More than 40% of the African captives brought to this country arrived there. Today, 80% of African Americans can trace their ancestry to this wharf.

A living memorial to those dismal days, the museum graciously pays homage to the people whose freedom permanently ended when they arrived on these shores and to the generations after them who would never know the taste of personal autonomy. In a secluded boardwalk outside the museum, sculptures of kneeling figures representing those who were held and perished in storehouses were especially moving.

Rather than looking at the period in isolation, IAAM expands its view to incorporate more contemporary African American culture both locally and nationally. It also devotes considerable space and effort in celebrating Black achievement post emancipation. The museum’s representation of a particularly distinctive subculture, the Gullah Geechee, proved particularly enlightening and gratifying. Isolated on sea islands off the South Carolina coast, the Gullah Geechee were able to retain a language, cuisine and a way of life removed from the larger society. Focusing so keenly on their exceptionalism, and exposure later to people tied directly to that community, only intensified curiosity about their unique culture.

This Land Calls Us Home

Through November 6, 2025

Atlanta Hartsfield International Airport

North Terminal T

Atlanta, GA

The International African American Museum

14 Wharfside Street

Charleston, South Carolina