If you’re functioning fully in a society that depends on the speed, convenience and pervasiveness of digitized communication, it’s likely you’ve made peace with some of its costs. Engaging with social media subjects us to unsolicited market-based scrutiny. Shopping for anything online, no matter how mundane, turns consumers into bundles of exploitable data. We shrug off these annoyances as the unfortunate price we pay to participate in a technology driven culture. Even when the sophisticated capabilities of technological advancement are absorbed into agencies of the state, the general tendency is to ignore the possible consequences of government actors possessing and abusing staggering computational power.

Artists though exist in a world of imagination and introspection where questioning and assessing everyday life leads to wellsprings of inspiration. Wrightwood 659’s newest exhibition, Difference Machines: Technology and Identity in Contemporary Art, uses digital art; or technology itself, to expose the consequences its generated.

Heralded in its early days as a neutral space blind to the differences that separate and divide us on our earthly realm, the digital sphere was promised to be much more equitable. A utopia of endless level playing fields. Today, with disinformation proliferating and doxxing commonplace, we know our lives online are not idyllic. The seventeen artists in Difference Machines take a closer look at how our digital realities collide and intersect with our personal identities. They embrace both naked truths and envision extraordinary possibilities. The results are astounding, making the exhibit a bonanza for the mind as well as the eye.

Their wide range of approaches and the many different ideas that spawn their work help explain why the artists presented in this exhibit are so exciting. For many of us who haven’t had the opportunity to experience digital art at its highest form, Difference Machines may even seem unprecedented. Some works, like Sean Fader’s Insufficient Memory, distinguish themselves by their purity and poignancy. Combing through often obscure archives, Fader created a database of “every LGBTQ+ person who was murdered in a hate crime” from 1999 to 2000. He then traveled to and photographed each of the nearly 100 murder sites he was able to document. The physical exhibit displays enlargements of several of the locations he photographed. Mostly depicting unremarkable rural and suburban scenes, they’re striking in how commonplace and ordinary they appear. He then provided a brief description of the person(s) murdered and the circumstances surrounding their death on back of each enlarged image. Juxtaposing these placid images with composed accounts of brutality create an immediate and powerful response. One that intensifies as you move from one image to the next. By uploading the photographs with the detail of their importance to Google Earth, Fader harnesses technology to build a “digital memorial”. The change in format from physical image to interactive map doesn’t diminish the work’s potency in the least.

Either resulting from their race, gender identity, ethnicity, sexuality or dis/ability, all of the artist in the exhibit come from communities that set them apart. Like Fader, one notable aspect of their identity is reflected in their art and drives how they use technology to express themselves. Bangladeshi -born Hasan Elahi’s compulsion to engage in self-surveillance was sparked by an unfortunate and unwarranted brush with the FBI. The encounter was the impetus for him to create Thousand Little Brothers, an expansive work that makes us rethink the who and why of surveillance. It also provides a graphic example of how much digital content one individual can generate over time.

Figures found in Skawennati’s animated film She Falls for Ages – image courtesy of ACMSIGGRAPH Art Show Archives

Some pieces are so beautiful that the meaning behind the message can take a second to discern. Saya Woolfalk’s Landscape of Anticipation 2.0, a looped video presentation of a future world, stuns with its size, brilliant color and the vibrancy of life that fills it. Of Afro-Japanese descent, the artist confides that she “gravitates toward utopian potentials” and creates figures that exist beyond race or gender. They can even extend beyond what it is to be human by inhabiting a space where all life is fused into a single connected existence. A consciously hypnotic piece whose appeal is enhanced by the ethereal music it emits, Landscape of Anticipation 2.0 casts a spell and causes you to genuinely consider extraordinary possibilities that might exist in some distant future. Because of the considerable infrastructure requirements needed to support this work, there are many museums and galleries who are prohibited from displaying it. Those constraints make the installation’s appearance in this exhibition all the more notable and appreciated.

Quite different, equally impressive and perhaps even more ambitious, Skawennati’s She Fall for Ages uses the latest media technique of machinima to upend notions of what futuristic constructs can look like. A Mohawk multimedia artist, Skawennati employs science fiction to craft an enchanting vision of how the earth might be redeemed from destruction. Reimagining the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) creation story, the artist builds a spare but enchanting existence that gives individuals remarkable agency to affect dramatic change. Expressed simply and directly enough to be understood and appreciated by children, the work enjoys universal reach and appeal. And, like most of the pieces in the exhibition, it also exists online.

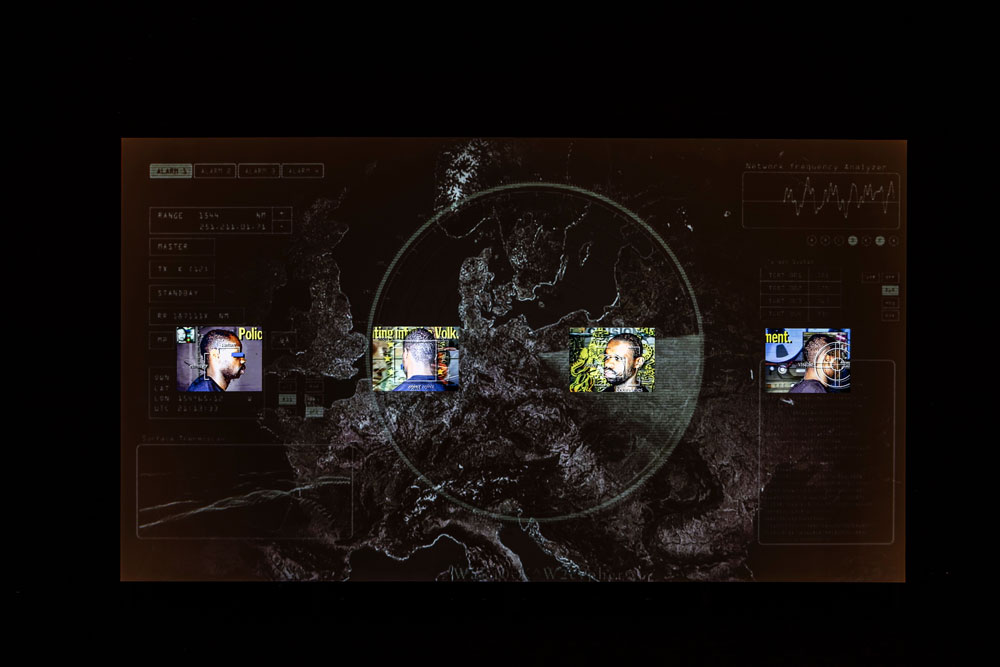

Keith Piper’s, Surveillance: Tagging the Other, highlights more scurrilous aspects of technology. Created in 1992 and anchored in the here and now, his work seems as relevant today as it was three decades ago. Across four monitors, a Black man’s head, suspended in space and slowly rotating, sits in the crosshairs of an assault weapon. The sound of news clips chronicling the “rise in racists attacks, antisemitism, and right wing tendencies in Europe” play in the background. British and Black, Piper shares the visceral response of perpetually being tagged, or targeted, for the basest of reasons. Using his art to expose and protest, he gives voice to anyone who finds themselves victimized for merely existing.

Organized by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, the exhibition also includes bioart experiments, digital games and 3-D sculptures that will arouse and delight your consciousness. Chicago is the last stop of the award-winning show’s four city tour.

Difference Machines: Technology and Identity in Contemporary Art

October 13 – December 16, 2023

Wrightwood 659

659 W Wrightwood

Chicago, IL 60614

Tickets: https://wrightwood659.org/exhibitions/difference-machines-technology-and-identity-in-contemporary-art/