Affirmation was photographer’s Kwame Braithwaite’s north star. Considered one of the defining lights of the Black is Beautiful movement of the 1960s, Braithwaite used his camera as a tool of uplift to celebrate self and to embrace African-American culture. In a career that began when he was just eighteen years of age and spanned seven decades, his artistic aspirations initially leaned toward music before being drawn to photography. The transition would lead him to use the power of the medium to promote Black pride, showcase Black achievement and encourage cultural self-determination. Kwame Braithwaite: Things Worth Waiting For, at the Art Institute through July, brings together a collection of photographs, film clips, archival slides, album covers and more in recognition of Braithwaite’s impact on contemporary photography and American culture.

By concentrating on work Braithwaite completed during the 70s and 80s, the exhibit highlights one of his most prolific periods. An arc of time that coincided with social unrest and racial tension, the gravity of national events seeped into the arts. Martin Luther King had just been assassinated a few years earlier, the Viet Nam war was nearing its end and the fallout of Watergate tested the viability of political institutions. It was in this environment that Braithwaite introduced a revisionist aesthetic through photography. Advocating that there is more than one standard of beauty, he used the fruit of his work to advance the validity of his belief.

Enterprises he initiated with his brother, Elombe Brath, would lay the groundwork for the direction he took with his photography. In 1956, the two founded the African Jazz Art Society and Studios (AJASS), a space created to explore music and dance celebrating the fullness of African American culture. A few years later, the brothers developed and introduced GRANDASSA models. By providing a venue to showcase the physical beauty of Black women, the brothers filled an immense longstanding void.

Of the two galleries making up the exhibition, the first devotes itself primarily to music and fashion. As seen in a serene image of singer and activist Abby Lincoln, where she sits regally in the center of the frame with her skirt flaring out like coronation robes, the two can be combined. There are also photographs of everyday life in Braithwaite’s native Harlem. Stylishly dressed in classic 70s fashions, attractive young couples quietly revel in one another’s company. Another image shows a shopper casually browsing African centric clothing along a city street. Each of the photographs carry a sense of easy self-assurance and natural contentment that contradict the more common projections of Black life during the era. Their power lies in the honesty of their simplicity and in their directness. Presented in black and white, there’s also an ingratiating purity about the photographs that’s both innocent and aspirational.

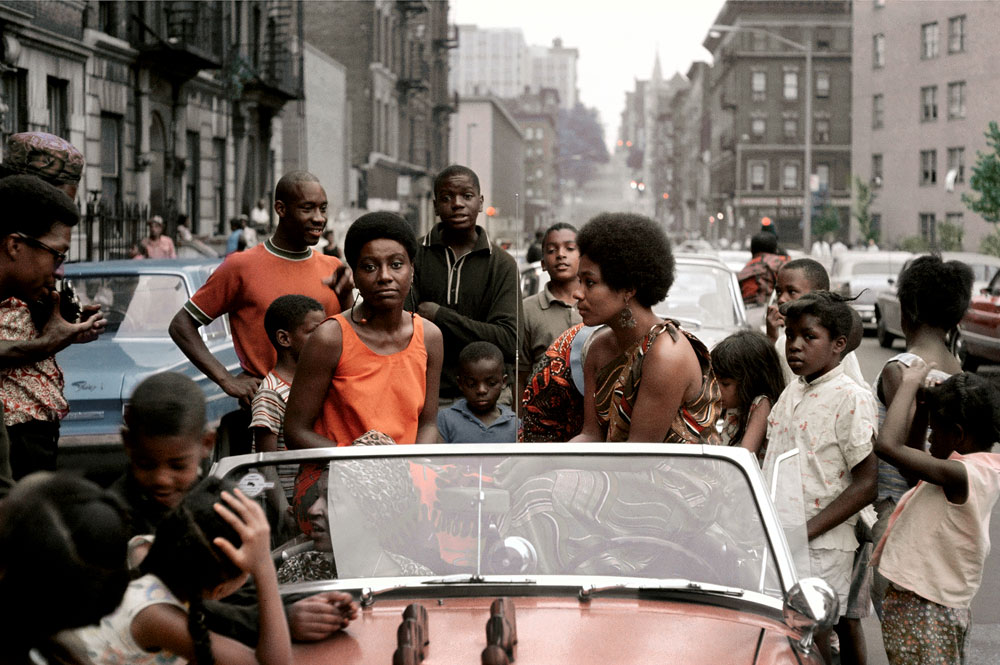

A different dynamic shines from a large color photograph filled with people gathered together on a special occasion. Two women in Afros sit partially high on the back seats of a small convertible, like dignitaries about to join a parade. Children and teenagers surround them. It’s Marcus Garvey Day in Harlem and the aura of celebration carries with it a pensive intensity that shrouds the photograph in a suggestion of melancholy.

Braithwaite took hundreds of photographs of celebrities and cultural figures. Those included in this show either achieve uncanny intimacy or reflect the magnitude of fame with exceptional power. The subject of several images in the exhibition, those of Stevie Wonder fall in both camps. Now seen fifty years in retrospect, they look back at the popular appeal of one of the biggest artists of the day and show some of the activities conscientious performers engaged in to enrich their community. A 1975 image of Bob Marley preserves a rarely seen energy. Off stage with his guitar under an arm at the Wonder Dream Concert in Jamaica, his face registers both surprise and suspicion. It’s impossible to determine what provoked the response, but beneath his expression is the unmistakable markings of vulnerability.

Featuring photographs taken after launching GRANDASSA models, Black female beauty dominates a long glamour infused wall. In close-up’s depicting beautiful women in large afros and full length photographs of women dressed in African or Africa inspired clothing, the images pay homage to Black womanhood. In another room, archival slides revolve on a projector chronicling people taking joy in being who they are and people famous for being who they are.

Kwame Brathwaite: Things Worth Waiting For

Through July 25, 2023

Art Institute of Chicago

Modern Wing

159 E. Monroe Street

Chicago, IL 60603

Monday/Friday/Saturday/Sunday 11am – 5pm

Thursday 11:00am – 8pm