Consider the two new exhibitions featured in Lincoln Park’s Wrightwood 659 like a fine dining experience. Something that’s best appreciated unrushed and with a receptive mind. That approach will leave you with a new appreciation for art’s ability to transcend language.

Impressively ambitious, The First Homosexuals looks at the elusive essence of sexuality from the vantage point of art. The show’s title suggests this could be a deep plunge into the nooks and crannies of cultural variation across the globe and throughout time. It’s not yet that. There are exceptions but the focus of the exhibition is from 1869 to 1935. The show will be return in a more expanded “Part 2” format in 2025. But even then, it’s hard to imagine it could be as comprehensive and its name implies.

Curated by Jonathan D. Katz, Associate Professor of Practice, Art History, Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, The First Homosexuals invites us to step away from the language we commonly use when we discuss sexual attraction and desire. The term homosexual came into being less than 200 years ago in 1869. When looking back in time and across the wide spectrum of humankind, how then was sexual exception interpreted? Especially in art. The First Homosexuals, with the input of Dr. Katz and more than twenty other scholars, responds to that question in thought provoking, enlightening and often beautiful ways.

Archetypes, Couples, Pose and Colonialism make up some of the nine sections that help organize the paintings, photographs, film recordings and drawing that fill the exhibition. No matter the theme in which it’s found, the collection’s art work is striking either for its subtlety or its frankness. Some pieces seemed so conventional, their placement in the exhibition had to be explained. There’s nothing explicitly sexual about the 1790 charcoal drawing from the French school of a languidly reclining male nude. It’s only after reading the wall text that you understand the radical nature of the image. Until that period, no one had taken the revolutionary step of depicting the male form in a pose formerly associated exclusively with the female body. Admiring the cool elegance of a late 19th century painting of a woman seated in a luxurious room is also quite benign superficially; until you learn the painting was done by the woman’s lover, Edith Emerson. Both pieces are like so many of the more formal renderings in the show. Aesthetically they’re accomplished pieces of representational art. But the subversive power of their message vies with, or exceeds, the strength of the image itself as a work of art.

Some of the pieces included in the show weren’t new but fit easily and well into The First Homosexual’s goal of highlighting sexuality’s fluidity. Ma Rainey’s big embracing smile beams out at us from the wall as her, Prove on Me Blues, plays softly from a speaker. She wrote the playful anthem of defiance in 1928, shortly after being busted for her participation in a female orgy. With lines like “Went out last night with a crowd of my friends, They must’ve been women cause I don’t like no men”, the quintessential blues singer thumbed her nose at convention and settled happily on her own interpretation of self-care. That spirit of claimed freedom could be found throughout the exhibit; revealing how entire societies can exist, and sometimes flourish, within societies.

Art can show what words can not say. It’s one of the triumphs of The First Homosexuals to give expression to how sexuality can be either very elusive or inextricably fixed; and how it can vary dramatically from person to person. David Paynter’s 1935 L’aprés-midi (The Afternoon), one of the show’s most significant paintings, doesn’t get its power from its suggestive implications. Instead, by hinting sexuality comes from a place deep within, it’s the eyes of one of the painting’s subjects that fire the imagination.

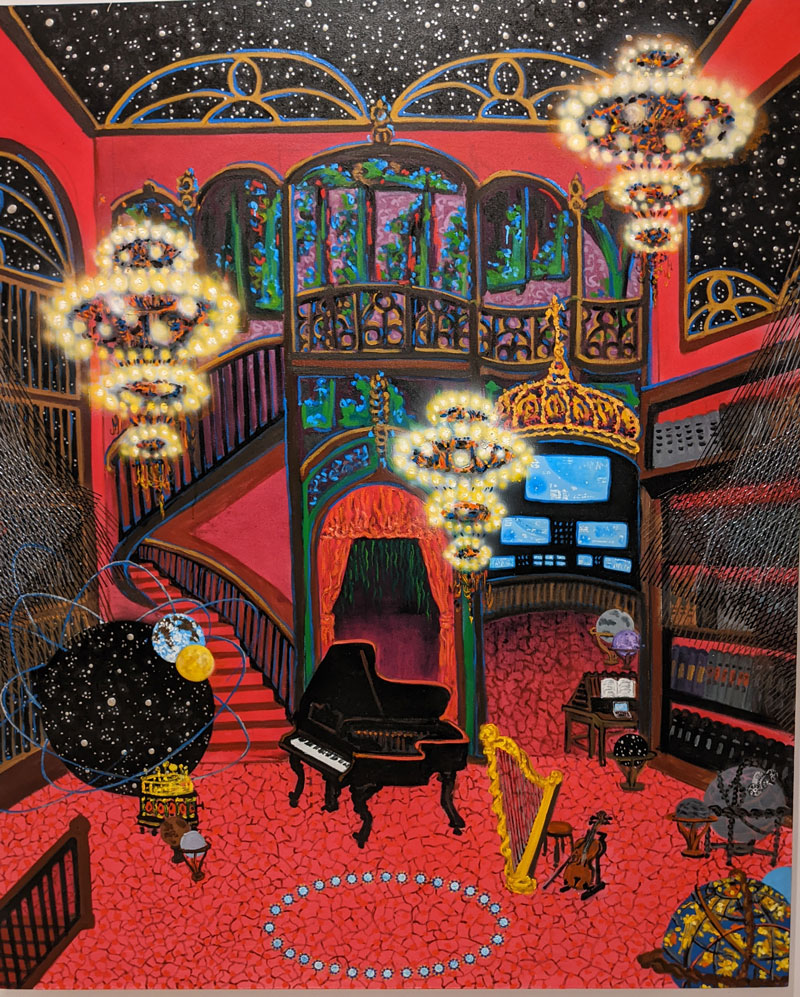

Celestial Stage, a celebration of Michiko Itatani’s art on the gallery’s upper two floors, taps into another way we see ourselves. This showcase isn’t concerned with how we see one another; but is instead fixated on “humanity’s mysterious place in the infinite universe.” By constantly placing the known in direct proximity to the unknown, Itatani encourages us to use our eyes and minds to find the balance between the two. Whether they’re bright with color or shrouded in cool detached mystery, it’s the artist’s wish that her work instill hope. Possibility certainly registers, and wonder. Many of her paintings depict rooms from bygone ages, so filled with object they’re virtually crowded, suspended in the vastness of space. It’s easy to get lost in what each item in the paintings might mean or represent. But ultimately, it’s the larger statements Itatani’s work make that are much more interesting.

The artist’s interest and potent ability to work with textures is also evident in the Celestial Stage review. Large and absorbing, her artistic musings on more conceptual planes are also entirely satisfying.

The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869 – 1930

Michiko Itatani: Celestial Stage

Through December 17, 2022

Wrightwood 659

659 W. Wrightwood Ave.

Chicago, IL 60614