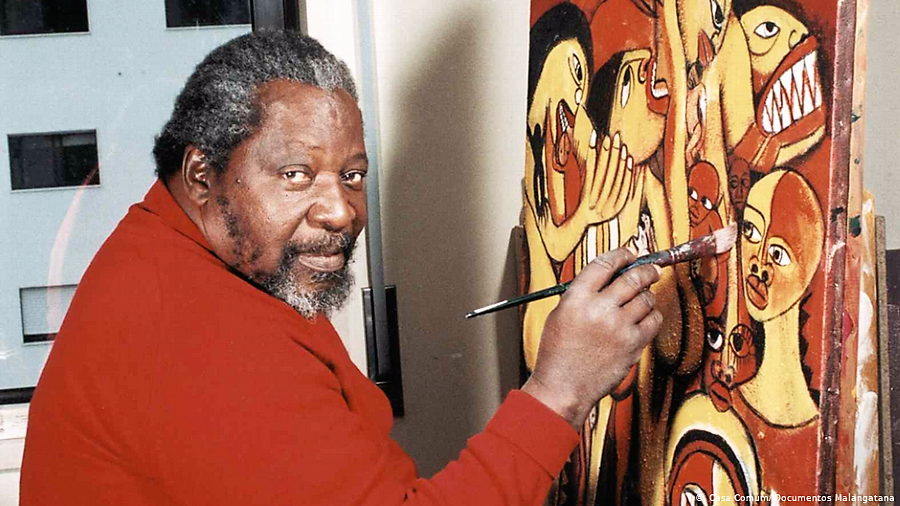

“People are selfish.” Malangatana Ngwenya used that phrase repeatedly in a film, Homeland, about his life and work a few years before he died in 2011. Commonly known simply as Malangatana, he rose to prominence and received international notoriety in the 60s and 70s for the force and power of his paintings that refused to adhere to a prescribed style or aesthetic of modern art.

Going his own way came with a cost. Born in Mozambique in 1936 and a member of the Ronga tribe, he grew from birth to adulthood under the colonial rule of the Portuguese. Portugal, like many colonial powers, required its territories assimilate its own culture and renounce native traditions and religions. The intense internal tension this created in Malangatana found release in his art. A wonderfully curated exhibition celebrating that work has been at the Art Institute since July and leaves soon on November 16th; giving you a few more weeks to admire Malangatana’s uniquely stirring contributions to arts universe.

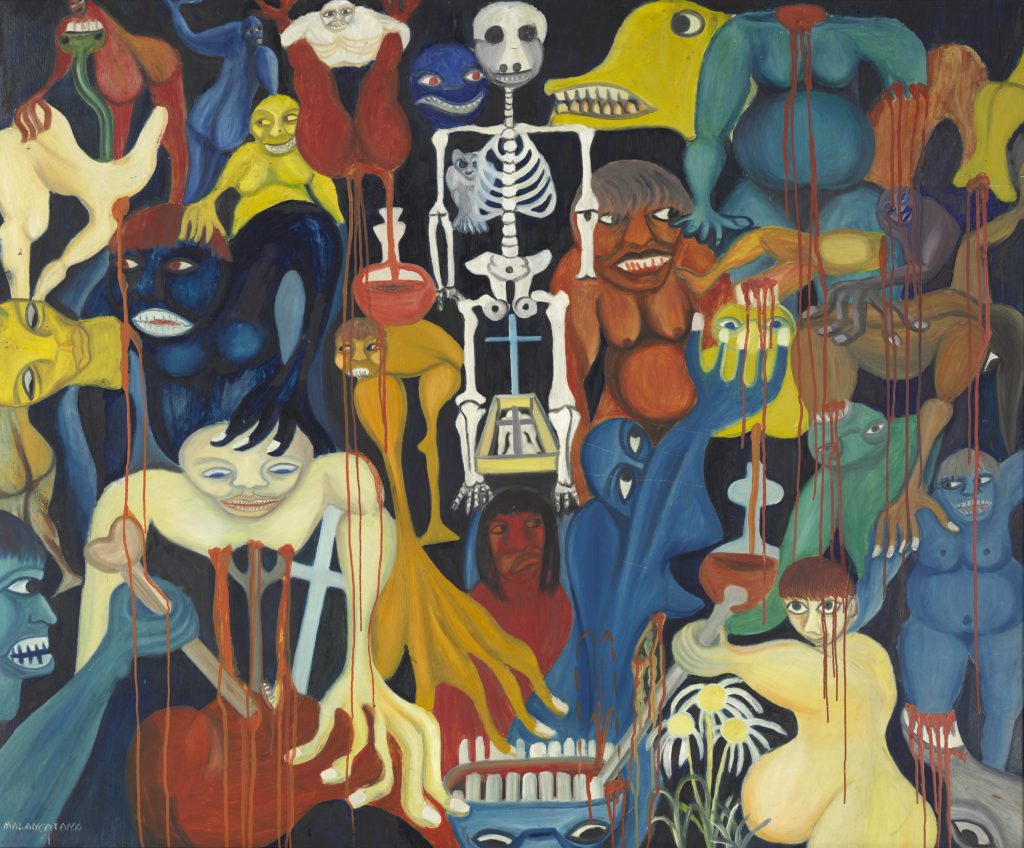

With just under 50 pieces in the show, it’s relative small scale still provides an engrossing range of his paintings’ themes and expressions. Nurtured in the traditional beliefs and customs of the Ronga people by his mother, Malangatana consciously incorporated core components of his indigenous culture into his art. Often that included the fantastical, the other worldly and a spiritual perspective both unfamiliar and unsettling to western eyes. These elements would be joined with images that challenged the veracity of Portuguese authority by questioning the infallibility and virtue of the colonizers religion, Catholicism.

The voice of dissent was to come to Malangatana. First, he had to discover who he was as an artist and gain confidence in pursuing a set direction. After moving from his small town to the city for work, he also looked for ways to do art. He got the opportunity to take art classes, found beneficial mentors and began to develop a sense of what his contributions could be. His early paintings revealed his talent and, because of the western thrust of his classes, tended to reflect European influences like cubism. Even then though a nativist note could be seen in his use of colors and his inclusion of images that evoked a mystic spiritual sensation. Many of his painting at that time were in oil on board rather than oil on paper; giving them a rugged accessibility and appeal.

Formal insurrection against Portuguese rule broke through the surface in 1964 with Malangatana’s work absorbing and reflecting the “anguish’ of the years that followed. Much of his works dance in beautiful colors and reminds you of the brilliant colors found in Jamaican tourist art. Malangatana colors don’t gleam as brightly nor is his message at all benign. The paintings are saturated with the depiction of the consequences of violence. Flowing blood and severed limbs tell the story of hard battles. In one corner of a painting you’ll find a woman folded over the corpse of a fallen brother, son or husband with the aftermath of carnage filling the rest of the work.

Malangatana ability to communicate so strongly through the eyes of his subjects remains one of his most enduring and appealing legacies. In 25 September II, a typical work where every inch of the painting throbs with immediacy and the tools and consequences of conflict, you get a sense of the individuals in the painting. Large, bold and so resolute they seem placid, the eyes of a mass of resistance fighters look out at the world like a wall of defiance. Their weapons are not guns but knives, daggers and machetes. Most are held in hands, one is imbedded in a skull and another stands from a gaping mouth. It’s one of the exhibits most transfixing paintings because it’s possible to make a personal connection to the people represented.

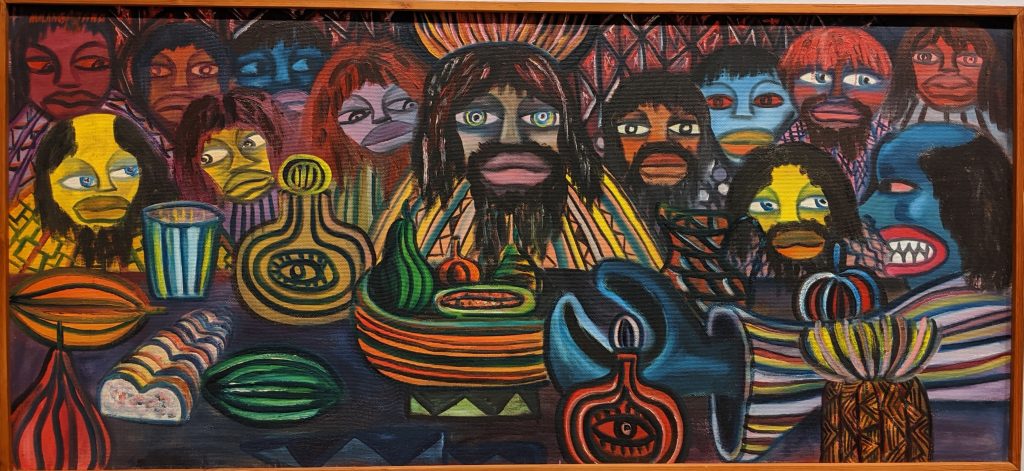

Eyes are just as absorbing and bold in one of the strongest reinterpretations of the Last Supper you’ll find. A commentary on betrayal and forgiveness, Malangatana completely transports da Vinci’s masterpiece to a different cultural context and fills it with a transcendent dignity and mystery. Colors brood and there’s no effort to obscure the identity of Judas.

Malangatana could have emigrated from Mozambique during the insurrection but didn’t. Suspected of having allegiances with the resistance, Portugal’s secret police imprisoned him for four years beginning in 1964. He still found a way to express himself through art. Color disappeared, replaced with the graphic starkness of black and white sketches that centered on individual suffering.

Even before liberation came to Mozambique in 1975, Malangatana was respected by his countrymen as artist of the people. By the time conflcts ended, he was hailed as an “artist of the revolution”. One of his largest paintings, The Cry for Freedom, completed two years before independence, combines many characteristics found in his body of work and even includes a self-portrait floating in the mélange.

The Art Institute exhibition not only brings attention to a notable contributor to modern art, it shows how art can be used to dramatically expose injustice, reimagine pre-existing art and rejoice in one’s own singularly unique heritage.

Malangatana: Mozambique Modern

Through Nov. 16th

The Art Institute of Chicago – Modern Wing

Nichols Bridgeway

Chicago, IL 60603