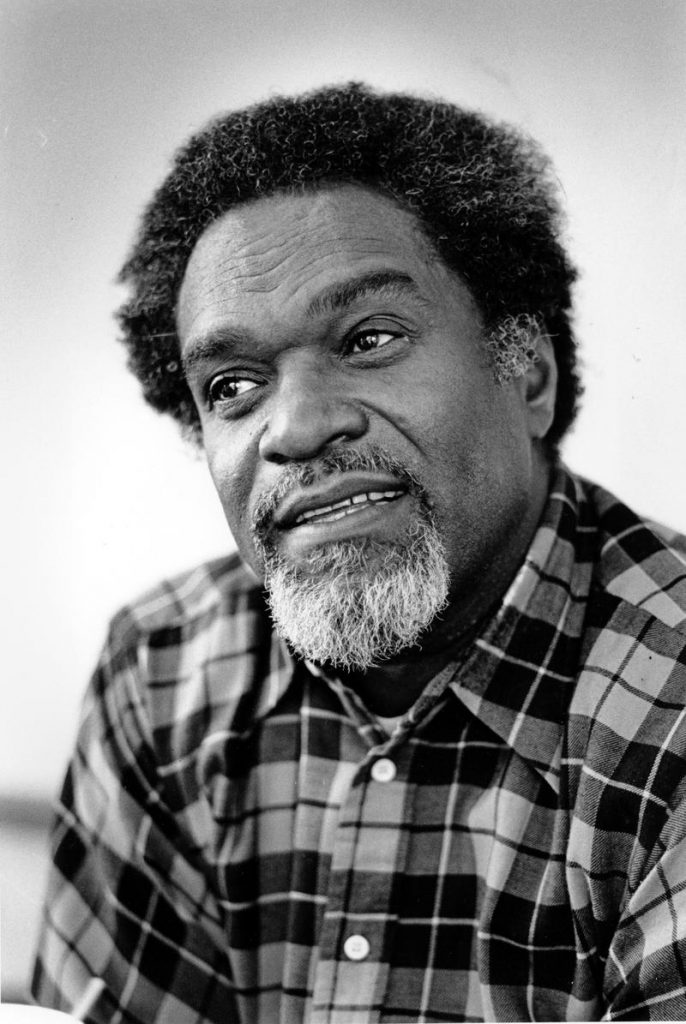

When Douglas Turner Ward wrote his pioneering one act play, Day of Absence, in 1965; he had a very clear intent. He wanted to write a play exclusively for a black audience. An audience that did not then exist. He was also working with a highly specific set of objectives. Expectedly, he wanted to write a play that spoke to the lives black people lived, but he also aimed to create a work that was implicit and allowed his audience to fill in the blanks. One that was subtle and edged with fine threads of sophistication. And just as importantly, he wanted to write something that did not put his audience to sleep.

He came up with two plays, both in one acts, Happy Ending and Day of Absence that played simultaneously at the St. Mark’s Playhouse in New York. Both plays grew legs and are regularly reprised on the contemporary stage.

When they were originally created 55 years ago, Ward also had to track down and recruit an audience by going anywhere the black public gathered; social clubs, union halls, beauty shops to rustle them up. His tactic worked and the productions played over 500 shows at the St. Mark’s.

Congo Square is only presenting Day of Absence on Victory Garden’s Christiansen stage right now. And as wonderful as it is, the current production won’t be running as long as it did when the play debuted back in ‘65. Making it even more of a must see. Even today it’s startling to see what Ward did with this jewel. A spare play with very few props, Day of Absence, like any top-tier theatrical creation intended for live performance, thrives on a gleaming story and fantastic characters. And it achieves everything Ward originally hoped to accomplish plus.

Taking an approach that says, “We know how you see us, now let us show you how we see you”, Day of Absence is all about reversals and looking at the world through different eyes. Normally, the cast is all Black. But this updated adaptation broadens what “black” is by making it anyone not white; resulting in cast made up of both brown and black performers.

The overriding constant is that the play is still performed in white face, (and lots of wigs) with minorities portraying whites in a small southern town.

Opening quietly, a couple of regular guys working in a mall are just getting their day started. Luke (Ronald L. Conner) and Clem (Kelvin Roster, Jr.) share small talk southern style and toss shout outs to regulars as they peruse the routine landscape of their work lives. Clem’s older and Teddy Bear homey, Luke’s younger, gruffer and lost in his cell phone. It takes a minute or two, more like several, but Clem finally picks up on something. Something that’s not quite right or out of kilter. Suddenly stricken, he realizes he hasn’t seen a black person all day. Half the population. Luke’s slower to accept something that ridiculous. Until he can’t do otherwise.

Performed as satire, Day of Absence chronicles what happens when a constant of life disappears. One that you may take for granted, resignedly tolerate or even benignly dismiss depending on your mood. More interestingly, it’s a story about how people react. What do they say and do in what quickly escalates into crisis and chaos.

Anthony Irons directed the production and achieved a master stroke by having his characters, or more precisely his characterizations, vie with the plot for overall strength. The way Ronald Conner portrays nonchalant insouciance is about as winning as it gets. Later we find him equally transfixing playing a completely different role. Roston, with his delicious phrasing and the pitch perfect softness of his drawl, is just as effective as Clem.

The action streams briskly through three backdrops. The mall, John and Mary’s bedroom and the mayor’s office. John (Jordan Arredondo) and Mary (Meagan Dilworth) make their discovery of the vanishing rudely when their new born wails plaintively through the night and there’s no one to tend to it. There’s no Kiki, no Black three-in-one, nursemaid housemaid cook, to intervene and relieve the stress of parenthood. Dilworth’s Mary is so preciously inept at doing anything useful you’re tempted to feel sorry for her. But that sympathy would be horribly misplaced. Dilworth still makes a splendid Mary whose only skill is to function as a household “decoration”. Arredondo as her husband fills his role to the brim with manly character and pragmatism. When he valiantly volunteers to go the hood to look for Kiki and finds nothing short of a ghost town where “not even a little black dog” could be sighted, he’s all business and entitled indignation.

Ward created the consummate repository for the town’s angst and ire in the mayor. And director Irons knew exactly how to shape the character as an unforgettable foil. Unflappable and supremely confident, the mayor’s sense of privilege and the power she insinuates take on regal dimensions. In the right hands and under the right direction, it’s a fantastic role and one that Ann Joseph fills beautifully. Ordinarily a male actor plays the part and Jackson is the last name of his female personal assistant/secretary/gopher. Here Jackson is the second role Mr. Conner inhabits so vividly and with so much virtuosity. Always on point and a bit self-consciously effete, he’s deferential to a fault and ever vigilant about watching his own back.

Ward shrewdly built a lot of humor into the play. And this effort takes advantage of every morsel. It even adds more zest causing the whole affair to frequently tip over into the hilarious. The perfume skit alone deserves its own baby Tony award. Despite the outright comedy, the underlying subtext couldn’t be more biting. Bryant Hayes as Clan and Kelvin Roston, Jr. in his dual role as Rev. Pious represent the true demons Ward is battling in his lasting contribution to the American stage.

This adaptation, cleverly updated with the playwright’s permission, makes it shine like new money.

Day of Absence

Through March 27, 2020

Victory Gardens Theater

2433 N. Lincoln Ave.

773-871-3000

www.congosquaretheatre.com